Alexander Calder designed a tiny circus. Marcel Duchamp’s legacy? Fits in a suitcase. And in postwar Paris, high fashion staged a comeback via haute couture dresses - each no taller than a mini baguette.

This week, we’re looking into the forgotten, surprising, and oh-so-very-cute world of miniatures in art. Because isn’t everything better mini?

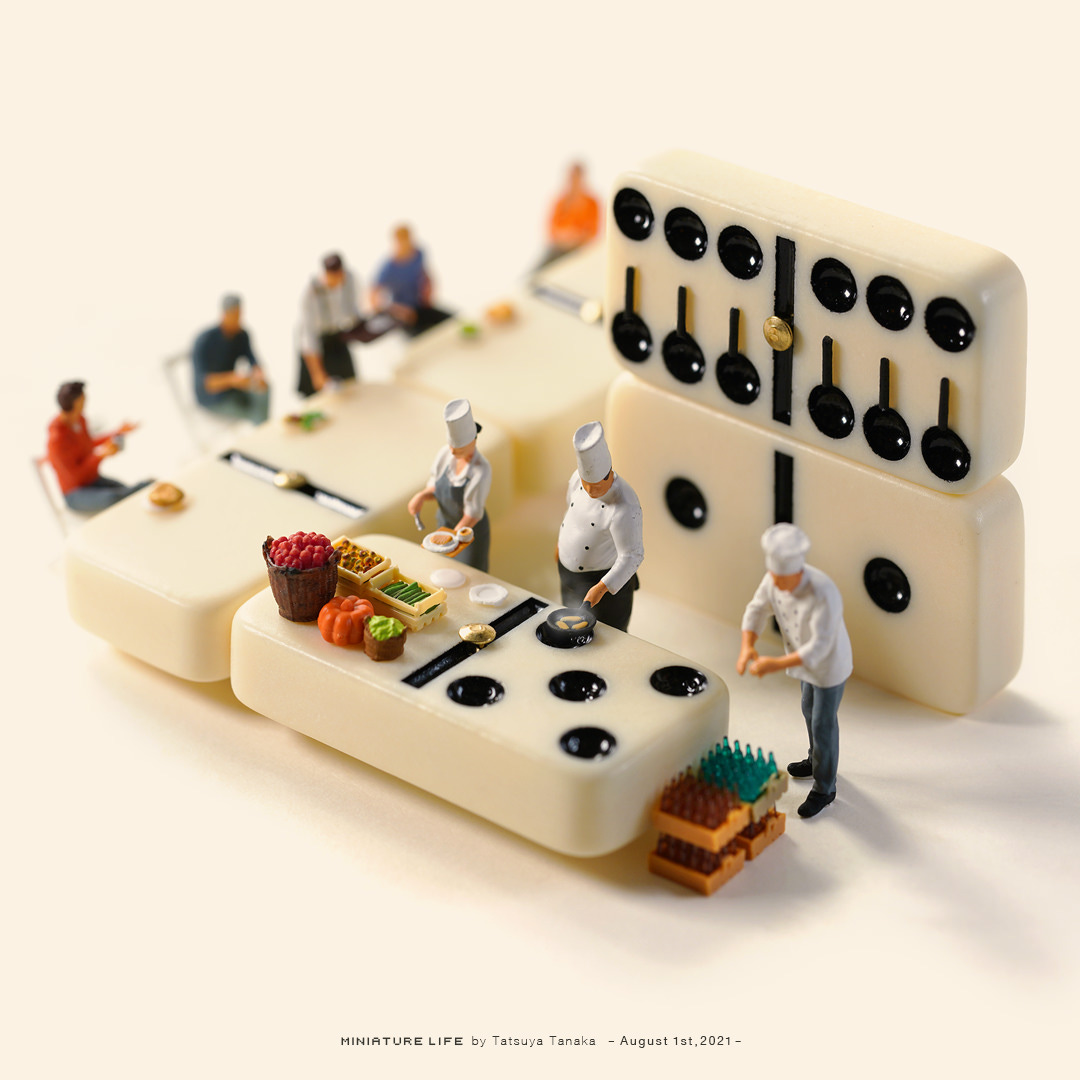

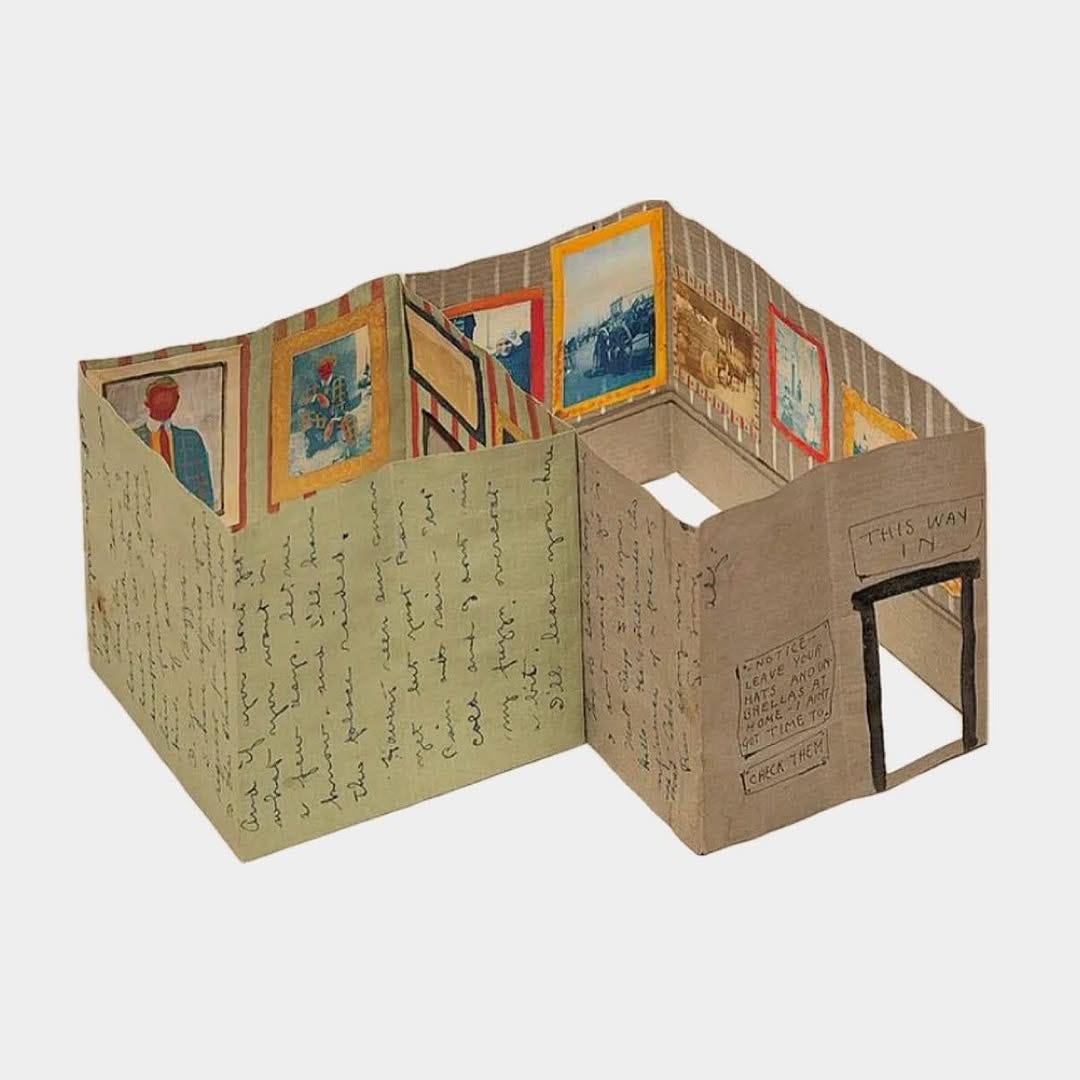

My Instagram algorithm knows I like tiny things. Who doesn’t? These Japanese miniature life sets are an instant DM. This little art show has matchbox-sized paintings. And my new happy place: an Upper East Side miniatures shop where everything fits in the palm of your hand.

Tiny art is viral eye candy. It’s clickable, it’s shareable, it’s adorable. But it didn’t occur to me that miniatures could be a serious art form - until I was doing research for my modern artist jewelry post & discovered Calder’s debut into the art world started with a teeny tiny circus (more on that below).

I began to wonder - what other mini art forms have been overlooked or forgotten, either because of the literal scale or because the high art world didn’t take them seriously beyond a cute “oooh and ahhh?”

It took a little digging (doll-sized shovels only), but discoveries were made…

Here are 3 great examples of miniatures in art that everyone should know about:

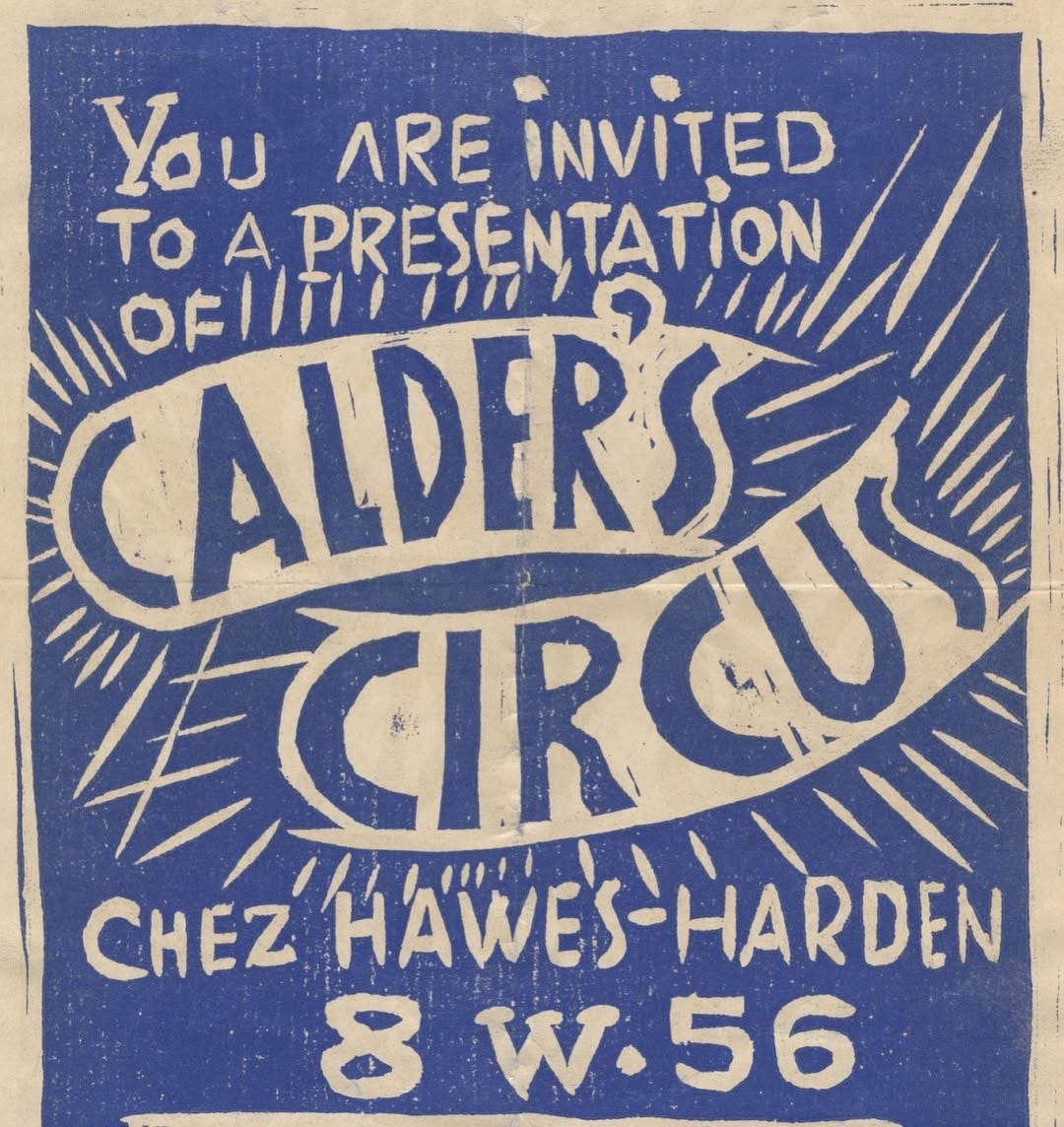

1. Alexander Calder’s Cirque Calder (1926-1931)

It’s 1926, and Alexander Calder has just moved from NYC to Paris with dreams of becoming an artist. His first major work? A beloved miniature circus, built from crumbled candy wrappers, a twisted egg beater, rhinestones, and wire. It came complete with flying acrobats, roaring lions, and a little clown who blew balloons. Tiny whimsy at its finest.

But circus wasn’t meant to sit still - no! It was a performance. Calder toted the whole thing around in a suitcase, staging shows for the café crowd of Montparnasse - acting as the ringmaster, puppeteer, and sound effects guy (all in one!).

Why the circus? His grandson explains:

“My grandfather grew up at the end of the golden age of the American circus (1871–1917), and as a young man, he studied the formalities of the circus arts with great intensity. In the spring of 1925, he spent two weeks illustrating the Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey Circus in New York for the National Police Gazette. When the circus relocated to its winter grounds in Sarasota, Florida, he followed it there and continued sketching.”

The golden age of the circus! I’m so in (reminds me: Ali LaBelle did a fantastic circus-inspired mood board that Calder would surely approve).

Word got out about Calder’s performances & the who’s who of bohemian Paris wanted in. Marcel Duchamp, Jean Cocteau, Man Ray, Joan Miró, and Piet Mondrian were all Circus-goers. The friendships formed here shaped his career - it was Duchamp, in fact, who gave Calder’s kinetic sculptures their now-iconic name: “the mobile.”

When Calder moved back to NYC, he took “Circus” with him - performing it at Park Avenue parties before it finally found its forever home at the Whitney Museum - where you can still see it today.

Here’s Calder’s infamous performance - if only I could hire him for my 30th bday -

Why is the circus worth remembering? It set the stage for everything Calder would become famous for - wire forms, kinetic magic, a sense of play and wonder.

Oftentimes, artists’ earliest work is the most formative yet forgotten about. It’s easy to remember Calder for his massive mobiles in the MoMa’s atrium but the quieter masterpiece? Something small. Handmade. Intimate!

A wonderful, tipsy little circus touted around Paris in a suitcase.

In many ways, Calder’s entire career came back to the playfulness he first found in the circus ring.

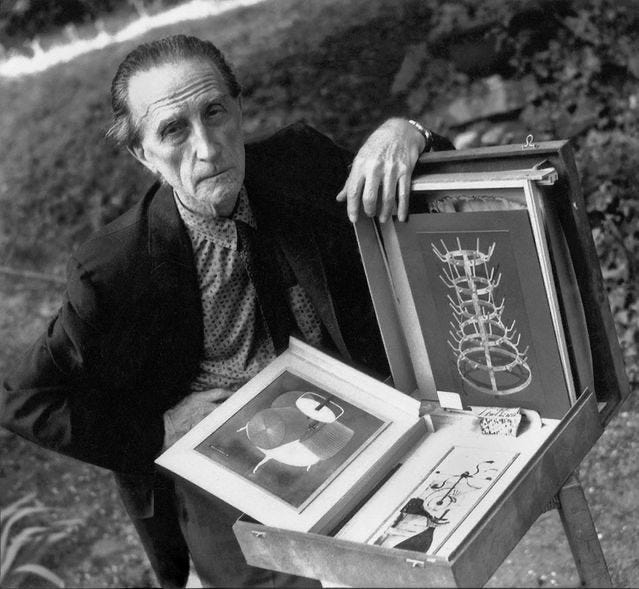

2. Marcel Duchamp’s Boîte-en-valise (1935-41)

“Everything important that I have done can be put into a little suitcase”—Marcel Duchamp

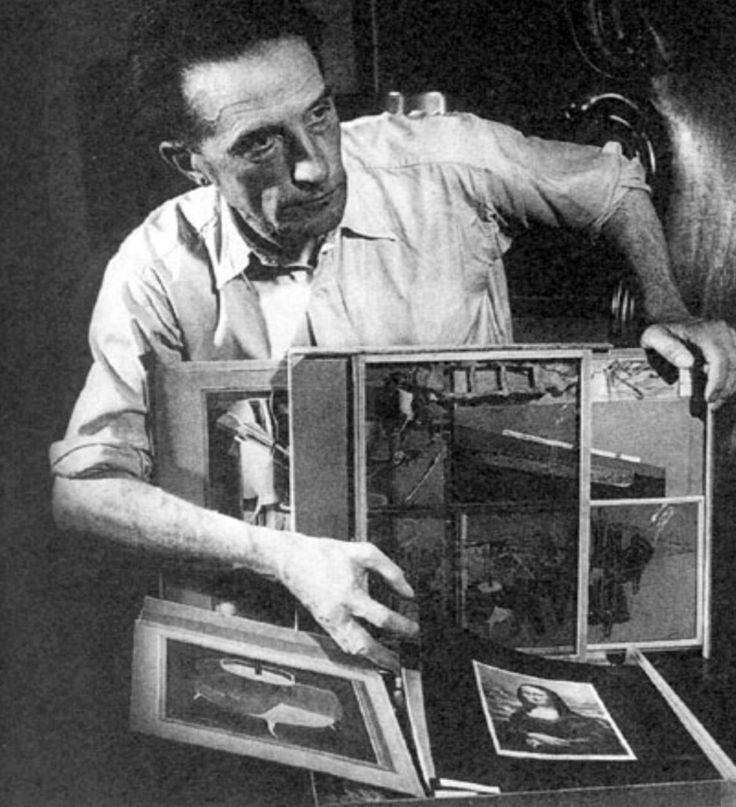

Not long after Calder carted his miniature circus around Montparnasse, Marcel Duchamp was bouncing around Paris and New York with a suitcase of his own. It looked like a simple traveling case - but inside? A mini museum. Meet Duchamp’s Boîte-en-valise.

Translation: “Box in a suitcase.” Inside were 79 tiny replicas and reproductions of his most famous works.

Back it up: You probably know Marcel Duchamp for his most infamous work: Fountain (1917) — aka the iconic urinal that became high art. It was part of Duchamp’s “readymades,” or his ~radical~ proclamation that art didn’t require making anything at all. A bicycle wheel. A bottle rack. A snow shovel. It shocked and horrified all at once (which we love).

By the time Duchamp created his suitcase, he had already caused quite a stir in the art world. The Boîte-en-valise - in its v classy Louis Vuitton case - was his way of showing off the hits. Full-size urinals and bike wheels aren’t exactly portable, so he shrunk them down.

But Boîte-en-valise wasn’t just a party trick - it was a strategic way to preserve and transport art on the brink of a war. It was 1930s Paris & borders were closing. Avant-garde art was famously being seized and destroyed - there is NO way Duchamp’s work would have passed inspection.

To make the first suitcase, he had to get creative - Duchamp posed as a cheese salesman (!) & traveled through Nazi-occupied France using a German-issued pass and a display case with secret compartments. Behind the faux cheese samples?! His mini artworks - smuggled through checkpoints under everyone's noses. Genius!!

When he finally got to NYC in 1942 (with suitcase in hand), Duchamp was ready to whip up more versions. He created around 300 versions of the Boîte during his life - each a little different & personalized for museums, collectors and friends (Peggy Guggenheim got one, of course).

It was a great exercise in self-promotion - the suitcases were essentially the first art girl’s online portfolio (Wix.com, anyone?!). He essentially took control and created his own retrospective while he was living - all in mini form. Conventional? Of course not - but what else would we expect from Duchamp.

3. Théâtre de la Mode: 27-inch dolls that saved Paris fashion post-war (1945-1946)

Let’s go back in time to 1945 Paris. World War II just ended and the city is in ruins. Food is rationed, fabric is scarce. What was once the capital of art and fashion is barely scraping by. Fancy evening dresses and glittery bags?! Who had the time.

Haute couture was in desperate need of a revival - so Paris’s most prestigious couturiers - Schiaparelli, Lanvin, Lelong, Balenciaga, the list goes on - put their heads together and came up with a (very tiny) idea. If there weren’t enough resources for a jaw-dropping fashion show, why not make a miniature one?

Enter the Theatre de la Mode. A traveling exhibit of 27-inch mannequins dressed in meticulous couture-level designs. Tiny handbags, tiny shoes, even tiny lingerie.

The show opened at the Louvre in Paris in 1945, and it traveled across Europe and the U.S. as a little fashionable temptress. It worked to remind people - French fashion exists! It’s still magic! You’re still magic! It helped inspire a future after the war.

As for the dress designers? The crème de la crème of couture designed for the show - Nina Ricci, Elsa Schiaparelli, Jeanne Lanvin - but my favorite part is the not-so-famous names…at least not yet. Among the rising talent was Pierre Balmain, who had just founded his own house in 1945 - this show helped introduce his designs to an international audience.

There was also a little-known designer you *may* have heard of: Christian Dior. At the time, he was working under the legendary Lucien Lelong - his name wasn’t on any labels, but he quietly contributed a few miniature looks (psst: they were a hint at what he’d do next).

Théâtre de la Mode gave Dior a place to test ideas that would soon become ~iconic~. Just two years later, he launched The New Look, established the House of Dior, and changed(!) fashion(!) forever(!). As The New Look documentary suggests, if Dior never did Theatre de la Mode, we might never have seen Dior’s “New Look.”

And the sets! The dolls were staged in dreamy theatrical sets - designed by artists like Christian Bérard (who served as the overall artistic director for Theatre de la Mode) & Jean Cocteau (btw - a guest of Calder’s circus a few years earlier).

What happened next?! One of the most fascinating parts of this story is what happened after the show - which for over two decades - was nothing. Théâtre de la Mode was essentially forgotten.

After its final stop in 1946, Théâtre de la Mode was quietly packed away in the basement of a Paris department store - that is until sugar heiress Alma Spreckels stepped in, helping transfer the entire collection to a new museum she supported - the Maryhill Museum - a hilltop mansion perched two hours outside of Portland, Oregon.

There it sat collecting dust until 1980, when Vogue’s legendary Susan Train rediscovered the dolls & became hooked. The collection went under an intense renovation and now has a permanent place at Maryhill - who wants to weekend trip there with me?!

Editor’s note: you MUST listen to the Articles of Interest podcast it - Avery Trufelman tells the full magical story of the 1980s revival - and I have to thank her for introducing me to the Théâtre de la Mode in the first place.

Sending you down these tiny rabbit holes before you go:

Bode’s Fall 2025 collection on tiny mannequins is VERY Theatre de la Mode

Follow Cold Picnic for miniature diorama rooms of their textiles staged in the most unexpected of places - a bathroom cabinet, an empty bookshelf, and a wall crevice.

The Eames Archives has a great piece re: how Ray and Charles built miniature models to sell dreams and tell stories - written by my internet friend Kelsey Rose

Speaking of Kelsey, she wrote a fab newsletter on another miniature I’d never heard about: The Museum of Drawers. I read it during my haircut, and I couldn’t stop googling afterwards - even my hairdresser became invested.

Want to see minis IRL? My friend & art historian Lauren Vaccaro has the scoop: “The Stettheimer Dollhouse on 5th Ave is incredible - it captures New York in a post-WWI era & includes mini versions of modern artworks specifically handmade for house.” Including - yes - our guy Duchamp!

And if you love all things small and magical, follow Allie Sullberg’s Substack The Museum of Small and Important Things. Every post is a little wonder.

Do you know any other miniatures that no one talks about? What are your favorite tiny art examples we need to know? Find me on insta at @rfranderson or comment below. Send us down the rabbit hole!

Delicioso post. <3 we love duchamp...

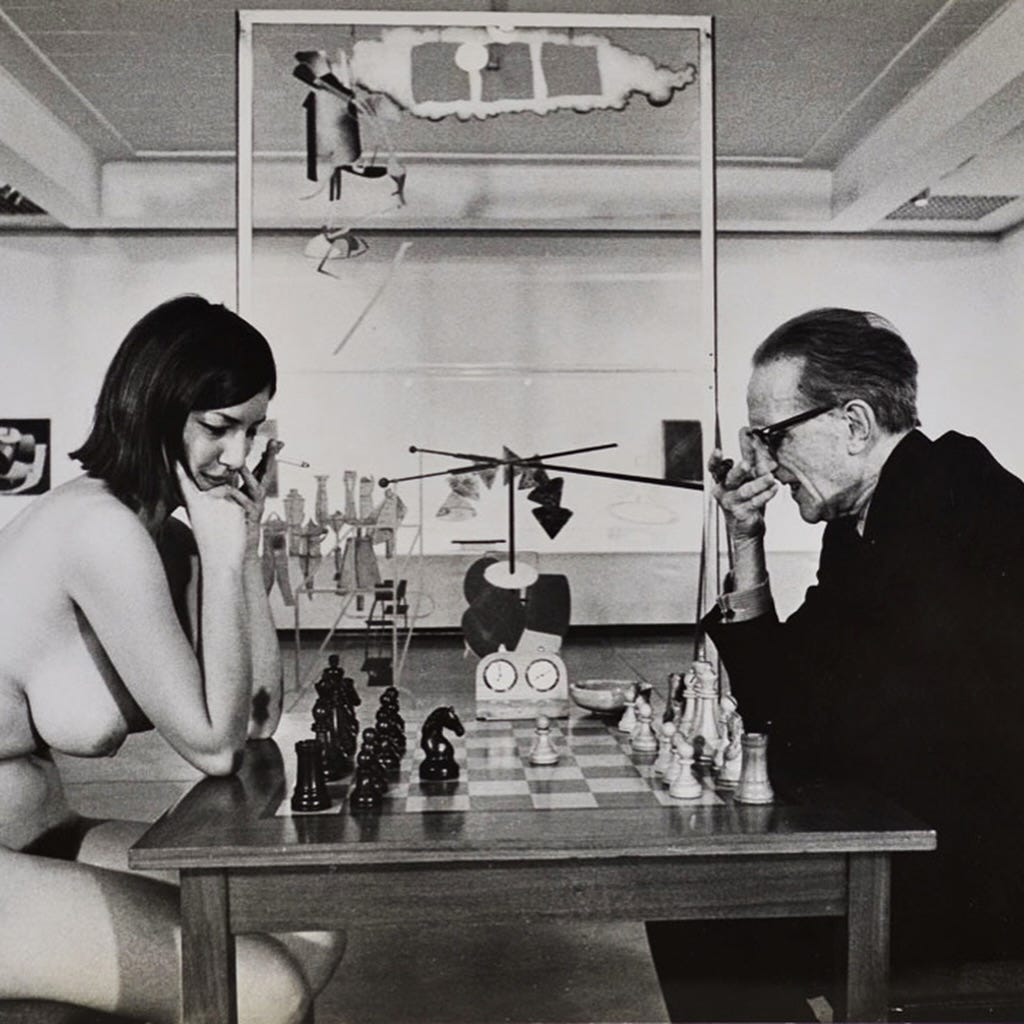

I didn't know I needed to see Babitz and Duchamp having a casual chess hang in the nude? (We may need the full story...) And those Dior minis!!!! Incredible.